The energy sector in MENA is undergoing structural changes with sustainability at its core to deliver on the region’s climate pledges. These changes are accompanied by a comprehensive set of economic and regulatory reforms to maintain a certain level of socioeconomic development to attain climate targets while considering each country’s energy security context, says the Arab Petroleum Investments Corporation (APICORP) in this new

Climate Justice: The North-South Divide

The energy sector in MENA is undergoing structural changes with sustainability at its core to deliver on the region’s climate pledges. These changes are accompanied by a comprehensive set of economic and regulatory reforms to maintain a certain level of socioeconomic development to attain climate targets while considering each country’s energy security context, says the Arab Petroleum Investments Corporation (APICORP) in this new report Climate Justice: The North-South Divide The main themes of COP27 are climate justice, balancing the trifecta of energy security, energy affordability and emissions reduction, as well as adopting a balanced approach between climate mitigation and adaptation finance.

A recent IMF article suggests that economies must collectively invest at least USD 1 Tn in energy infrastructure by 2030 and USD 3 Tn to USD 6 Tn across all sectors per year by 2050 to mitigate climate change, a formidable and unattainable sum for feeble economies already reeling from the impacts of COVID-19 repercussions. These countries are seeing themselves as having to pay for eradicating legacy GHG emissions that the developed industrial nations have caused over the past century. Although the global south is prone to severe impacts of climate change, the ability of these nations to finance climate change mitigation/adaptation will be limited.

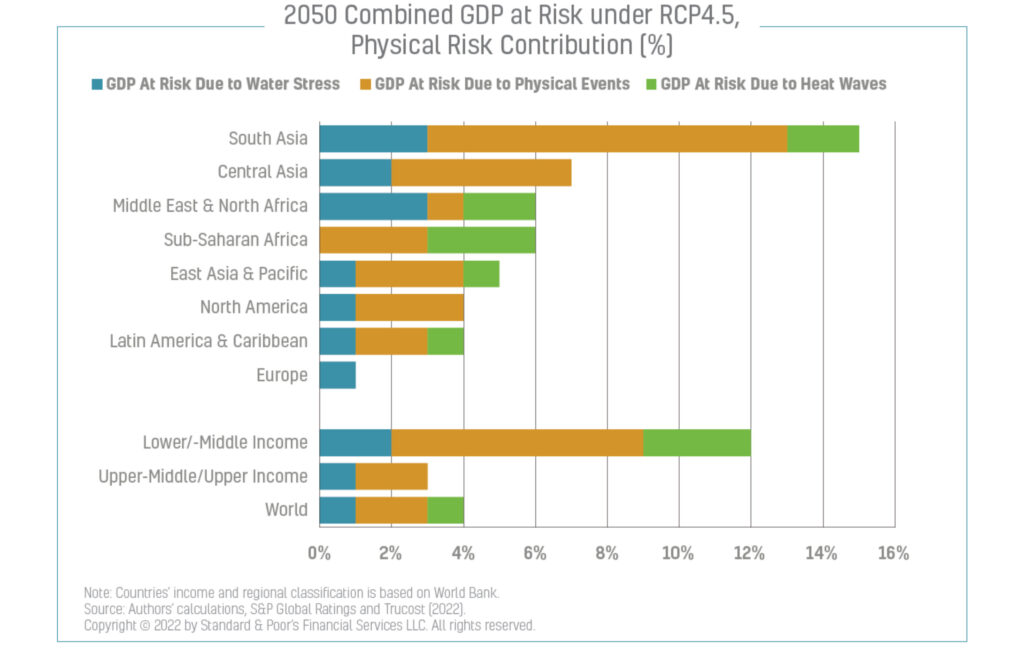

The MENA region has a vested interest in combating climate change. IPCC Climate models project that the average annual temperature could increase by almost 5°C in the region before the end of the century under the high emission scenario2. The World Bank’s calculations also show that lower & middle-income populations in the region will take the largest hit from physical climate risks.

On the other hand, public debt burdens have been accumulating since 2020 where the gross public debt in MENA crossed USD 1.4 Tn. With continuing global inflation and interest rate hikes, the ability of MENA governments –with the exception of KSA, UAE and Qatar– to finance the energy transition is very low.

Balancing the Trifecta: Energy Security, Energy Affordability, and Emissions Reduction

Countries around the world are facing the greatest energy crises since the 1970s. In October 2022, the UN secretary general stated that emissions must fall by 45% in the next eight years to avoid a climate catastrophe. This comes in a year where countries around the world are switching back to burning coal for power generation (after the historic pledge of COP26 to phase down the usage of coal) – sending coal

prices to record highs – as the spill-over from energy shortages affected fertilizer and food prices, raw material, and logistics costs.

In a volatile global economy battered by COVID, chronic global inflation, and the lowest agricultural productivity in a decade, developed economies have been hardly managing energy market tightness by paying more for their energy consumption, rationalizing energy consumption, bailing-out defaulting utility companies and subsidizing consumption. In developing economies, subsidy phase-outs had to be postponed and, in some countries, special social protection subsidies had to be injected to avoid destabilizing the entire state. In poor nations –where the energy crisis and its spillovers already jeopardized the entire social stability– governments had to ask for emergency aid from the international community. According to a 2022 study by the UN WFP, in just two years, the number of people facing acute food insecurity or at high risk increased by more than 200 million from 135 million in 53 countries pre-pandemic to 345 million in 82 countries today, mostly in developing countries.

For developing countries, the issue is much more complex, as they need to meet rising demand for affordable energy while simultaneously adapting to their vulnerability to adverse climate impacts, and above all of this, play their role in mitigating future climate change through decarbonisation.5 In this context, MENA countries’ progress in energy transition has been exemplary for emerging and developing economies, and driven by the following realities:

First, MENA economies have been challenged –with varied degrees– even before Covid-19 crisis. The region is highly vulnerable to global warming effects mainly, rising sea levels, and desertification, and hence has a genuine interest in climate action. On the positive side, the region is blessed with an excellent profile of scalable & affordable renewables, particularly in solar and wind. MENA conventional energy exporters recognize their responsibility in meeting global energy security needs in a new decarbonized world, and are using hydrocarbons windfall to advance investments in decarbonisation (e.g. CCUS). On the other hand, countries with no hydrocarbon resource significance are using renewables to decrease their energy import bill while still meeting their energy needs, and also eyeing clean energy export potential. The region –as a whole– targets capturing a strong future market share of renewable energy exports (Hydrogen, Ammonia, green electricity).

A Balanced Approach between Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Finance

Climate mitigation has been the focus of multilateral negotiations for decades over how to slow or arrest GHG emissions that contribute to climate change. Now, developing countries having long pressed for developed countries’ financial assistance against severe storms, heat waves, floods, and other physical risks. Climate adaptation will be at the forefront of COP27 discussions after mitigation shortages have resulted in damages and even human losses. A 2022 Oxfam report shows that the average annual extreme weather-related emergencies rose more than 800% over the last two decades, with developed countries contributing only 54% of risk packages required. The economic cost of extreme weather events in 2021 alone was estimated to be USD 329 Bn globally, the third highest year on record.

This is nearly double the total aid given by developed nations to the developing world that year. Historically, fossil fuel extraction, industrialization, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been.

skewed toward a small number of countries. These “high-income” countries, as identified by the World Bank, are responsible for 44% of cumulative CO2 emissions from fossil fuel extraction, manufacturing, land use, and forestry since pre-industrial times. Their share of the current global population, by contrast, is just 14%.

Developing countries coming to COP27 with the aim of claiming right to compensation for tangible losses and damages from climate events, especially given the legacy failure of developed countries to meet their climate funding commitments to date. Calls for loss & damage obligations on the part of the global north will be stacked on top of pleas for financial assistance for emissions reductions.

The level of global adaptation funding committed in the context of the COP has so far inadequate in comparison to the scale of current and future needs. The official Adaptation Fund, created in 2001 to finance adaptation efforts in developing economies, has circa USD 1 Bn in funds available, mostly earmarked for initiatives to prevent loss of life, such as early warning systems.

The drive for adaptation carries a sense of urgency that mitigation never could, in that the associated physical risk is visible and quantifiable. The blended finance approach that received so much attention at COP26 was largely discussed in the context of mitigation, but it may prove equally well or even better suited to adaptation.

prices to record highs – as the spill-over from energy shortages affected fertilizer and food prices, raw material, and logistics costs.

In a volatile global economy battered by COVID, chronic global inflation, and the lowest agricultural productivity in a decade, developed economies have been hardly managing energy market tightness by paying more for their energy consumption, rationalizing energy consumption, bailing-out defaulting utility companies and subsidizing consumption. In developing economies, subsidy phase-outs had to be postponed and, in some countries, special social protection subsidies had to be injected to avoid destabilizing the entire state. In poor nations –where the energy crisis and its spillovers already jeopardized the entire social stability– governments had to ask for emergency aid from the international community. According to a 2022 study by the UN WFP, in just two years, the number of people facing acute food insecurity or at high risk increased by more than 200 million from 135 million in 53 countries pre-pandemic to 345 million in 82 countries today, mostly in developing countries.

For developing countries, the issue is much more complex, as they need to meet rising demand for affordable energy while simultaneously adapting to their vulnerability to adverse climate impacts, and above all of this, play their role in mitigating future climate change through decarbonisation.5 In this context, MENA countries’ progress in energy transition has been exemplary for emerging and developing economies, and driven by the following realities:

First, MENA economies have been challenged –with varied degrees– even before Covid-19 crisis. The region is highly vulnerable to global warming effects mainly, rising sea levels, and desertification, and hence has a genuine interest in climate action. On the positive side, the region is blessed with an excellent profile of scalable & affordable renewables, particularly in solar and wind. MENA conventional energy exporters recognize their responsibility in meeting global energy security needs in a new decarbonized world, and are using hydrocarbons windfall to advance investments in decarbonisation (e.g. CCUS). On the other hand, countries with no hydrocarbon resource significance are using renewables to decrease their energy import bill while still meeting their energy needs, and also eyeing clean energy export potential. The region –as a whole– targets capturing a strong future market share of renewable energy exports (Hydrogen, Ammonia, green electricity).

A Balanced Approach between Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Finance

Climate mitigation has been the focus of multilateral negotiations for decades over how to slow or arrest GHG emissions that contribute to climate change. Now, developing countries having long pressed for developed countries’ financial assistance against severe storms, heat waves, floods, and other physical risks. Climate adaptation will be at the forefront of COP27 discussions after mitigation shortages have resulted in damages and even human losses. A 2022 Oxfam report shows that the average annual extreme weather-related emergencies rose more than 800% over the last two decades, with developed countries contributing only 54% of risk packages required. The economic cost of extreme weather events in 2021 alone was estimated to be USD 329 Bn globally, the third highest year on record.

This is nearly double the total aid given by developed nations to the developing world that year. Historically, fossil fuel extraction, industrialization, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been.

skewed toward a small number of countries. These “high-income” countries, as identified by the World Bank, are responsible for 44% of cumulative CO2 emissions from fossil fuel extraction, manufacturing, land use, and forestry since pre-industrial times. Their share of the current global population, by contrast, is just 14%.

Developing countries coming to COP27 with the aim of claiming right to compensation for tangible losses and damages from climate events, especially given the legacy failure of developed countries to meet their climate funding commitments to date. Calls for loss & damage obligations on the part of the global north will be stacked on top of pleas for financial assistance for emissions reductions.

The level of global adaptation funding committed in the context of the COP has so far inadequate in comparison to the scale of current and future needs. The official Adaptation Fund, created in 2001 to finance adaptation efforts in developing economies, has circa USD 1 Bn in funds available, mostly earmarked for initiatives to prevent loss of life, such as early warning systems.

The drive for adaptation carries a sense of urgency that mitigation never could, in that the associated physical risk is visible and quantifiable. The blended finance approach that received so much attention at COP26 was largely discussed in the context of mitigation, but it may prove equally well or even better suited to adaptation.

One important venue of climate adaptation that is overlooked is energy efficiency. A 2022 IMF paper8 states that improving energy efficiency brings a significant reduction in CO2 emissions and at the same time strengthens energy security, with considerable energy savings on the consumption side.

A Spectrum of Tools to Reduce GHG Emissions

The energy sector in MENA is undergoing structural changes with sustainability at its core to deliver on the region’s climate pledges. These changes are accompanied by a comprehensive set of economic and regulatory reforms to maintain a certain level of socioeconomic development to attain climate targets while considering each country’s energy security context.

On the policy front, MENA countries are prioritizing capacity building and empowering institutions to be able to plan, prepare and react to climate change. Climate policy coherence and integration are the building blocks of any effective regulatory reform.

On the financing front, net-energy importers in MENA are suffering

from fiscal distress and debt burdens as a fallout from the COVID pandemic,

increasing commodity costs, high-interest rates, and a looming global economic recession.

These countries are pursuing strategic partnerships with MDBs and international

financial institutions to help finance mitigation and adaptation actions to

remain on track to realizing their climate pledges. With the climate action

price tag estimated at USD 275 Tn over the next 30 years (USD 9 Tn/yr.) for a

2°C scenario, MENA net-energy importers will only be able to reduce their GHG

emissions conditional to international financial support as reflected in their

submitted Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

One important venue of climate adaptation that is overlooked is energy efficiency. A 2022 IMF paper8 states that improving energy efficiency brings a significant reduction in CO2 emissions and at the same time strengthens energy security, with considerable energy savings on the consumption side.

A Spectrum of Tools to Reduce GHG Emissions

The energy sector in MENA is undergoing structural changes with sustainability at its core to deliver on the region’s climate pledges. These changes are accompanied by a comprehensive set of economic and regulatory reforms to maintain a certain level of socioeconomic development to attain climate targets while considering each country’s energy security context.

On the policy front, MENA countries are prioritizing capacity building and empowering institutions to be able to plan, prepare and react to climate change. Climate policy coherence and integration are the building blocks of any effective regulatory reform.

On the financing front, net-energy importers in MENA are suffering

from fiscal distress and debt burdens as a fallout from the COVID pandemic,

increasing commodity costs, high-interest rates, and a looming global economic recession.

These countries are pursuing strategic partnerships with MDBs and international

financial institutions to help finance mitigation and adaptation actions to

remain on track to realizing their climate pledges. With the climate action

price tag estimated at USD 275 Tn over the next 30 years (USD 9 Tn/yr.) for a

2°C scenario, MENA net-energy importers will only be able to reduce their GHG

emissions conditional to international financial support as reflected in their

submitted Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

One important venue of climate adaptation that is overlooked is energy efficiency. A 2022 IMF paper8 states that improving energy efficiency brings a significant reduction in CO2 emissions and at the same time strengthens energy security, with considerable energy savings on the consumption side.

A Spectrum of Tools to Reduce GHG Emissions

The energy sector in MENA is undergoing structural changes with sustainability at its core to deliver on the region’s climate pledges. These changes are accompanied by a comprehensive set of economic and regulatory reforms to maintain a certain level of socioeconomic development to attain climate targets while considering each country’s energy security context.

On the policy front, MENA countries are prioritizing capacity building and empowering institutions to be able to plan, prepare and react to climate change. Climate policy coherence and integration are the building blocks of any effective regulatory reform.

On the financing front, net-energy importers in MENA are suffering

from fiscal distress and debt burdens as a fallout from the COVID pandemic,

increasing commodity costs, high-interest rates, and a looming global economic recession.

These countries are pursuing strategic partnerships with MDBs and international

financial institutions to help finance mitigation and adaptation actions to

remain on track to realizing their climate pledges. With the climate action

price tag estimated at USD 275 Tn over the next 30 years (USD 9 Tn/yr.) for a

2°C scenario, MENA net-energy importers will only be able to reduce their GHG

emissions conditional to international financial support as reflected in their

submitted Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

On the technological front, there is a plethora of elements shared

among MENA countries that serve as implementation mechanisms to achieve the

targeted GHG emissions reduction. For countries aiming at decarbonizing their

energy sector; energy efficiency, CCUS (carbon capture utilization and/or

storage), blue & green hydrogen, methane management, renewables &

energy storage lie at the heart of their strategic plans to reduce GHG

emissions.

Energy Efficiency: Several initiatives are being implemented to reduce energy

consumption in targeted sectors, such as upgrading home appliances and air

conditioning units, optimizing feedstock utilization in petrochemicals, enhancing

the transportation fleet fuel economy, phasing out inefficient and used

light-duty vehicles, and improving the thermal efficiency of power generation

assets. Reducing energy consumption before scaling up energy supply is a

strategic tool that will help MENA countries achieve their NDCs. Energy subsidy

reform and amending regulatory frameworks will be essential to integrate energy

efficiency measures in various segments of the economy.

Carbon Capture Utilization & Storage (CCUS): Capturing CO2 emissions at the point

source for conversion into value-added products or storage in geological reservoirs is a critical technology for climate pledges. Net-energy exporting

countries are building upon their experience in enhanced oil recovery (EOR)

programs to advance the uptake of CCUS technologies and scale up their

deployment. CCUS hubs will leverage the concentration of the manufacturing

industry, proximity to sinks, and transport infrastructures in a circular

economy.

Currently, less than 30 large CCUS facilities are in operation

globally that capture around 40-50 MtCO2 per annum. Investments over the last

ten years amounted to around USD 10 Bn, less than 0.5% of the USD 2.9 Tn

investments in renewable technologies over the same period. Greater

international engagement is required to overcome obstacles that keep CCUS from

reaching the required scale. These range from large upfront costs, energy

losses, poor market signals and regulatory hurdles, to public acceptance issues

and safety concerns.

Blue &

Green Hydrogen: In light of the gradual energy transition towards a low-carbon

future in the region, blue and green hydrogen molecules will play a central

role due to their versatility as clean energy vectors for domestic use and

exports. According to IRENA’s 1.5°C scenario, hydrogen could meet up to 12% of

final energy consumption by 2050. Global hydrogen demand is expected to

increase from the current 90 MTPA in 2020 to almost 300 MTPA in 2050, according

to IRENA. By leveraging its strong potential, the MENA region is

well-positioned to supply around 10% to 20% of the global hydrogen markets by

2050.

In addition to its prospective role as a large-scale energy storage medium, hydrogen can be optimally utilized to decarbonize the hard-to-abate energy-intensive industries where electrification proves to be challenging. Pilots, research, and demonstration projects will be prioritized to improve technology maturity and lower costs in the aviation, maritime shipping, refining & petrochemicals, and hard-to-abate industries. For the MENA region, the most adequate near-term applications are the petrochemicals & refining industries (which currently depend on grey hydrogen and can shift to cleaner hydrogen vectors), steel and aluminum smelters, ammonia, and methanol. In the medium to long term, large-scale seasonal energy storage, long-haul transportation, and maritime shipping are prospective applications.

In the medium term, blue hydrogen proves to be a more attractive option to the MENA region. Blue hydrogen can be produced at a relatively low cost, and it will slightly disrupt the IOC/NOC’s existing business models. This is a central metric in the energy transition journey since hydrocarbon producers will play a key role in decarbonizing the upstream oil and gas sector and help reach net-zero targets by mid-century. Blue hydrogen can yield very low greenhouse gas emissions, only if methane leakage emissions do not exceed 0.2% with close to 100% carbon capture. For green hydrogen, the two main elements that need to be assessed are the cost of electricity from renewable energy sources and electrolysis. The MENA region has a highly competitive advantage in generating low-cost renewable electricity with high-capacity factors reaching 20%.

The levelized cost of renewable electricity in the region has reached world-record levels nearing USC 1.04/kWh (in the 600 MW Al Shuaiba PV IP project in KSA). However, due to the supply chain disruptions resulting from the pandemic over the past two years, the downward trend of renewable electricity costs is expected to invert temporarily before returning to its low levels by 2023-2024. As for electrolyzers, the technology risk resides in scaling up to a multi-GW scale that can be operated with intermittent renewable energy sources at high efficiencies. It is expected that the cost curve of green hydrogen will decline with time, and it will be cost-competitive with blue and grey hydrogen by 2030.

Methane Management: Considering its global warming potential, methane emission management is central to climate pledges. Measures include reduced flaring in the oil and gas industry, recovery, and subsequent utilization for power generation and production of petrochemicals. Currently, KSA, UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco, are all members of the Global Methane Pledge, a coalition established in COP26 with currently 100 countries representing nearly 50% of total global methane emissions. The coalition pledges to voluntarily work to reduce global methane emissions at least 30% by 2030, which could eliminate over 0.2˚C warming by 2050.

Renewables: Renewable energy systems have been gaining momentum across MENA driven by ambitious national targets, technology cost declines, and increasing investments toward low-cost and low-carbon technologies. The national renewable energy targets set for 2030 –ranging between 15% and 52% of electricity generation by 2030 portray the governments’ will to double down efforts and increase the share of renewables in the energy mix. As of 2020, the total installed capacity of renewable energy in MENA crossed 10.6 GW, almost double the capacity of 5.4GW in 2010.

Renewable Energy Targets in Selected MENA Countries

MENA countries with abundant renewable energy sources are accelerating their renewable energy plans to achieve their renewable energy policy ambitions while reducing domestic consumption of fossil fuels. Integrating renewables in their generation mix is part of a shared policy objective to diversify the power mix with low-cost, low-carbon energy vectors while maintaining the security of the power supply. Countries with robust renewables potential aim to reduce dependence on fossil fuel imports and integrate low-cost renewables into domestic grids.

Morocco and Jordan are currently at the forefront of renewable energy deployment in MENA, achieving their short-term policy targets. Morocco has reached almost 40% of its installed capacity from renewable energy in 2021, meanwhile, Jordan has achieved nearly 20% of its generation capacity. Other countries such as Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, and Oman have relatively low renewable energy generation, but the share is expected to witness a significant hike with large capacities planned and committed in the project pipeline.

The increase in renewables in MENA is mainly driven by utility and distributed solar PV, onshore wind power, and other energy sources such as CSP, geothermal and hydropower. The MENA region is expected to add around 33 GW of renewables by 2026 (by installed capacity), with around 26 GW as utility and distributed solar PV.

Energy Storage: Meeting the national renewable energy targets requires scaling up and systematic integration of variable renewable energy (VRE) systems into the power grid which in turn necessitates deployment of energy storage solutions (ESS) for firming the power capacity, building flexibility, and ensuring power systems stability. ESS also plays a critical role in managing intermittencies of VREs and in mitigating potential power supply disruptions while providing ancillary services.

The pace of integration of energy storage systems (ESS) in MENA is driven by three main factors: 1) the technical need associated with the accelerated deployment of renewables, 2) the technological advancements driving cost competitiveness of ESS, and 3) the policy support and power markets evolution that incentivizes investments.

Although the energy storage market in MENA is bound to grow, several barriers exist that hinder the integration of ESS and ramping up of investments. Financial, regulatory and market barriers need to be addressed via policy tools that shall lay the foundations for an evolved power market to integrate the deployed ESS.

Strong Pipeline of Low-Carbon Energy in MENA by 2030

The MENA region has a pipeline of USD 257 Bn in low-carbon energy projects by 2030. These include projects are different stages of development, where the planned low-carbon energy projects (at the pre-FEED stage) make up around 71% of total projects by net value.

The low-carbon energy sectors are witnessing accelerated project activity that will contribute to achieving climate pledges in MENA. The sectors include renewables (solar PV, wind, hydro), hydrogen, nuclear and waste-to-energy.

For project investments at both planned and committed stages of development, solar PV leads with a 50% share by project value, followed by hydrogen (21%), nuclear (14%), and wind (10%). Hydropower and waste-to-energy projects both constitute 5% of total projects by value.

On a MENA regional level, low-carbon energy projects are mostly concentrated in North Africa (59%), followed by the GCC (38%), and the Levant (4%) by project value.