Annual upstream oil and gas investment needs to rise by 28% to reach $640 billion by 2030 to ensure adequate global supplies, according to a new report published by the International Energy Forum (IEF) and S&P Global Commodity Insights, the leading independent provider of information, analysis and benchmark prices for the commodities and energy markets.

Introduction: What a Difference a Year Makes

The state of the global economy and the energy sector has been transformed since our last upstream investment report (Investment Crisis Threatens Energy Security, December 5, 2021). The economic outlook for the near-term has deteriorated significantly while the geopolitical risks, and price volatility, across the energy sector have surged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For the time being, long-term demand uncertainty has been overshadowed by turmoil impacting near-term supply and demand. On the supply-side, there are many outstanding questions about the depth and duration of a reduction in Russian production. On the demand side, there are many outstanding questions about the depth and duration of a global economic slowdown and how much China’s lifting of COVID-zero policies will offset sluggish demand elsewhere.

For policymakers, security of supply has re-emerged as a top priority. However, there is lingering uncertainty as to whether increased interventionism by governments in energy markets are a symptom of extraordinary circumstances in 2022 or a strategic shift that will transform into long term policies, market structures and price formation.

Market upheaval has led to higher and more volatile energy prices, resulting in record profits for oil and gas producers. After decades of lackluster stock performance and free cash flow, oil and gas companies are now outperforming every other major industry. Prices for long-dated futures (the back-end of the forward curve) appear to have decisively broken above $70 per barrel for the first time since the 2014 collapse. This has shifted the primary constraint on investment from capital availability to producers’ willingness to invest. As long as crude prices remain above $70 per barrel, there are enough profitable oil and gas reserves and projects to meet demand over the next decade, but the primary uncertainty is whether companies will commit sufficient investment to develop them.

The failure to increase and sustain investment in oil and gas upstream could lead to recurrent price shocks across commodities caused by the disparity between the slower-moving demand transition and the rapidly thinning supply buffer resulting from insufficient investment and geopolitical developments. This will result in increased price volatility across the energy complex and adverse economic consequences. Further, the combination of short-term price volatility and long-term demand uncertainty could further deter investment and further exacerbate volatility, with resulting energy insecurity inviting further government interventions.

New challenges and hurdles have emerged in the past year that are no less difficult than the obstacles we highlighted in December 2021. While oil prices ended 2022 at nearly the same level as the end of 2021 – the world is a different place. There is a lot more capital available for the upstream industry, but also acute short-term uncertainty. More than anything else, 2022 may have marked the end of the era of perceived energy abundance and the restoration of energy security. In this new energy world, investment has a critical role to play.

Investment in 2022 and Beyond

Global upstream investment rebounded in 2022

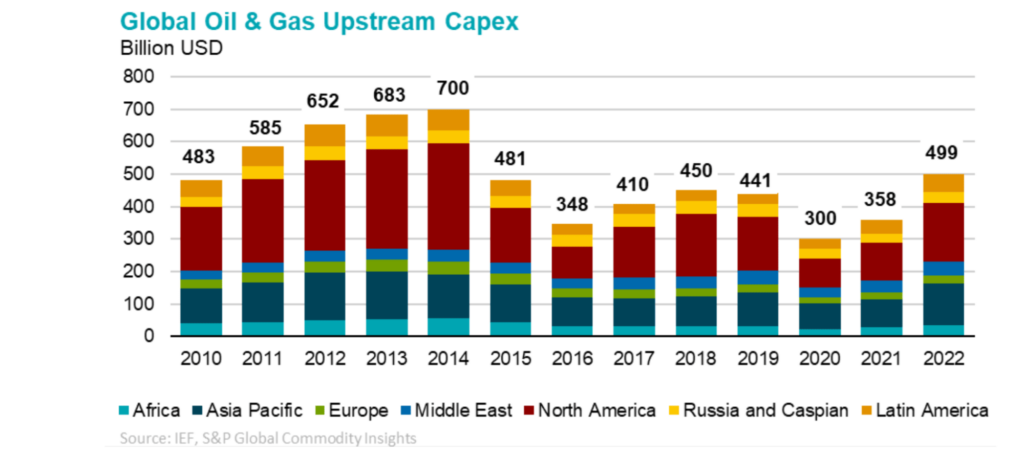

Oil and gas upstream capital expenditures rebounded by 39% ($141 billion) in 2022 to $499 billion – the highest level since 2014 and 13% above 2019’s pre-COVID level. Upstream capital expenditures in North America increased the most, rising by a robust 53% ($61.7 billion) year-on-year.

Increased spending reflects both increased costs and increased activity. Cost inflation was up 15-20% year-on-year in 2022, with more expected in 2023. While the global rig count is up ~22% year-on-year, it is still ~10% below 2019 levels. The industry has achieved significant improvements in capital efficiency over the past decade, but a high-cost environment means the sector will need even more investment than previously expected to ensure adequate supplies.

Our previous upstream investment report highlighted how 2022-2023 would be crucial years for financing projects. In 2022, nearly 2.2 million barrels per day of new capacity was approved or sanctioned – falling short of 2019’s high. In line with pre-pandemic trends, companies are still favoring small, modular, or phased projects over megaprojects (a single large-scale project with peak production of >500 thousand barrels per day with new infrastructure).

Notably, there are still no new greenfield megaprojects planned in the next five years despite of higher prices. In contrast, almost 250 small- to medium-scale projects are expected to begin by 2030, assuming companies move forward with investment. These projects require less capital, have shorter payback periods, and are more insulated from long-term risks.

If upstream capex fails to accelerate, the risk of markets facing a period of substantive supply shortfalls in the medium-term rises significantly. Recent market events and trends have dealt producers a sudden cash injection but also eroded many of the oil market’s supply buffers (commercial and strategic inventories and OPEC+ spare production capacity). Without traditional supply buffers, demand in the medium-term will need to be primarily met through increased investment in existing and new production.

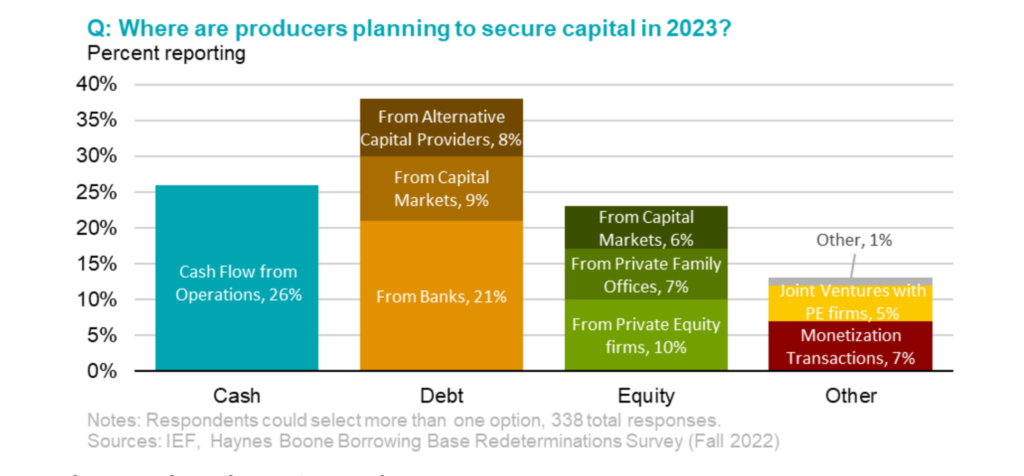

Primary hurdle for investment has shifted from capital availability to willingness to invest

This year’s record profits mean companies can afford to invest from operating cash flow, shifting the major constraint to companies’ willingness to invest. This is a significant change from recent years when the primary constraint on investment was capital availability due to weak cash flow, reliance on external capital, and waning investor appetite.

Whereas the challenge through most of the 2015-2021 was mainly prioritizing limited capital in a low commodity price environment, the challenge for investment in 2022 and beyond consists of how to allocate excess capital in a high(er) commodity price environment.

Seven of the largest global IOC’s reported free cash flow deficits every year except one between 2013 and 2020. The aggregate net free cash flow for the same group of IOCs between 2000 and 2020 equaled a deficit of $104 billion, but those deficits have been erased by record profits in the past two years. Major IOCs saw a record $97 billion surplus in 2021 that grew to an estimated $173 billion surplus in 2022. The surplus in 2022 is more than three times greater than the largest annual surplus experienced in a 20-year period between 2000 and 2020.

After prioritizing returns to shareholders, share buybacks, and debt repayment, companies still have record levels of free cash flow. The question is, will companies re-invest? If so, where? And if not, why? This entails company-level decisions to re-invest proceeds into upstream operations (existing or new developments) or divert windfalls to other ends, be they returns to shareholders and stakeholders or low-carbon/alternative investments. These decisions will be complex and depend on a number of factors including shareholder and stakeholder priorities, regulatory environment, existing operations, geography, in-house expertise, etc.

Many oil and gas companies face investor pressure to use cashflow from fossil fuels to invest in lower carbon options such as renewables and hydrogen. However, the sector also understands the cyclical nature of the business and that profits today do not guarantee profits tomorrow. In addition, some NOC’s may have governments that want to use the windfalls to boost their domestic economy. Other companies will not want to overcommit or base project economics on today’s environment knowing that while short-term energy security concerns have clearly increased and improved the near-term profitability, the long-term trajectory of hydrocarbon demand remains dictated by ambitious energy transition objectives. With most green-lit projects likely to produce well into the 2030s, the lack of long-term demand certainty remains a potent deterrent for investment, particularly for longer-term prospects such as exploration.

Willingness to invest remains the key variable only as long as profits remain high. If profits fall due to lower prices or policies (such as windfall taxes) – then capital availability becomes a key constraint again. There is still negative investor sentiment and other hurdles to obtaining external capital.

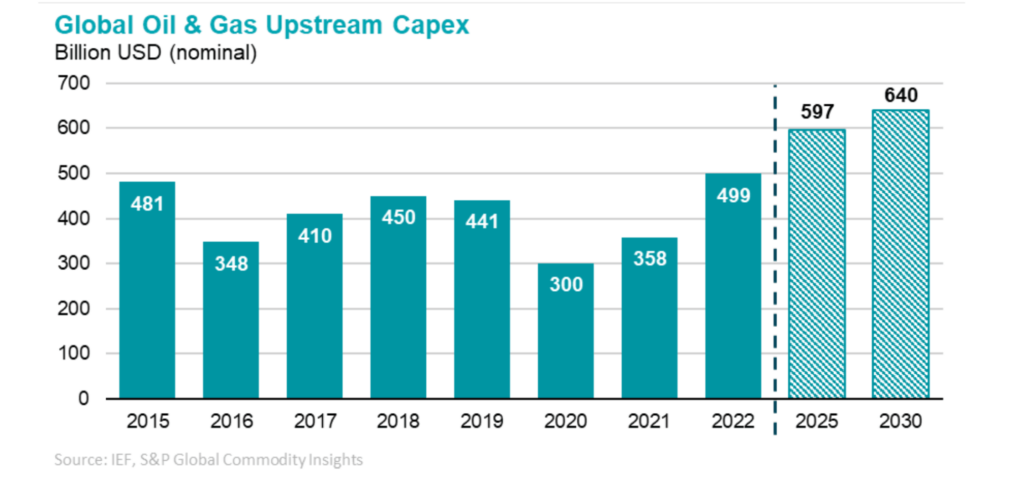

Upstream investment will need to increase to $640 billion annually by 2030 to meet future demand and offset declining production

While upstream investment in 2022 returned to an eight-year high and posted the largest year-on-year increase in history, it will need to rise even further to stave off a global supply shortfall this decade. Annual upstream investment will need to increase from $499 billion in 2022 to $640 billion in 2030 and a cumulative $4.9 trillion between 2023 and 2030 to meet market needs, even if demand growth slows toward a plateau. This is a significant ask from investors and companies, but one that has become critical in light of the 2020-2021 downturn and erosion of supply buffers in the market.

Continued upstream investment is needed just as much, if not more, to offset expected production declines than to meet future demand growth. Without additional drilling, we estimate that non-OPEC production would decline by 9 million barrels per day by 2026 and 17 million barrels per day (or 31%) by 2030.

Slowing Economy and Monetary Tightening Add to Investment

Challenges but Also Provides Opportunities

For an industry tasked with jump-starting upstream investment after stalling in 2020-2021, the broad-based slowdown in the global economy in 2023 and compounding tightening in global monetary conditions present clear challenges to both the demand outlook and access to capital.

However, unlike previous economic downturns, commodity prices are likely to remain elevated in light of supply concerns and geopolitical pressures, shielding industry returns even amid slowing demand. Additionally, as China unwinds COVID-zero policies, pent-up demand in China may partially offset some of the weakness caused by slowing economies elsewhere.

This presents a critical opportunity for the sector. In our previous investment report, we highlighted that the investment challenge was primarily a mismatch in velocity, with the recovery in upstream investment post-pandemic lagging global demand recovery. The slowdown in global demand over the latter part of 2022 and at least part of 2023 imposes some restraint on demand and affords some time for supply to catch up. But that will require operators to look through complex short-term economic risks.

Global spare production capacity will remain limited in the near-term

Traditionally, tight markets have found relief by drawing inventories, utilizing spare production capacity, or ramping-up short-cycle production (U.S. shale). Over the past twelve months, markets relied heavily on all four but have yet to find sustainable breathing room that would ease supply concerns. Strategic and commercial inventories have been tapped extensively and are below the 5-year average in most regions, and U.S. producers are tempering growth despite higher prices. All that remains is global spare production capacity.

Current global spare production capacity is at only ~2.0-2.5 million barrels per day; nearly all of it is held by Saudi Arabia and UAE. Global spare capacity rarely falls below 2.0 million barrels per day for any extended period. With a few notable exceptions, Gulf producers typically maintain a buffer to increase production in unexpected supply outages and emergencies.

Saudi Arabia plans to increase capacity to 13.2 million barrels per day (from their current 12.2 million barrels per day) by 2027, and UAE plans to expand to 5 million barrels per day (from 4.2 million barrels per day) by 2027. However, actual production increases will depend on OPEC+ policy and their desire to maintain their traditional safeguard.

Energy Security and Energy Transitions

Energy security needs to be accepted as a long-term issue

Energy security is back at the forefront of policymakers’ minds, leading to a more accommodating stance towards exploration and consumption in some countries but investors look longer-term and need regulatory and policy certainty. If policies for energy security are viewed as temporary measures, they will not spur the investment needed. The re-emergence of energy security helps break the cycle of the energy abundance mindset and leads to a more accommodating environment for investment.

Long-term demand uncertainty remains a key constraint on investment

Traditionally, decisions to invest in long-cycle upstream projects consisted of balancing economic considerations such as full-cycle breakeven prices and above-ground risk affecting developments.

Now, investment decision-makers must also consider if demand will still be there over the lifetime of a specific project and the impact of government policy changes.

While short-term demand and supply concerns have overshadowed long-term concerns recently, long-term demand uncertainty remains a key constraint on investment.

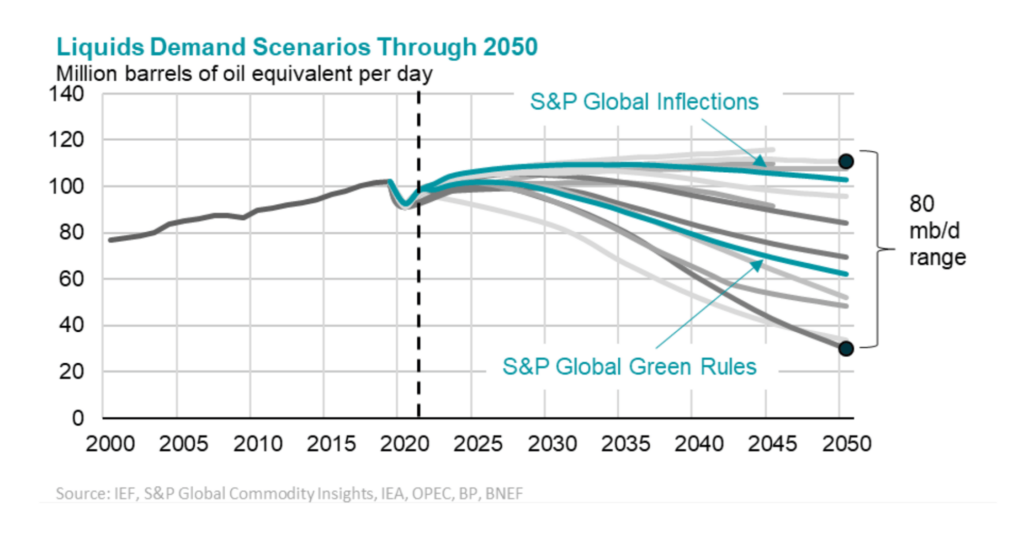

Of the various long-term forecasts and their varying scenarios, the difference between oil demand in the highest and lowest case for 2050 is 80 million barrels per day. The range in outlooks is equal to ~80% of today’s market – a massive divergence.

Long-cycle projects that would come online in the mid-2020s are meant to produce well into the 2030s and often beyond into the 2040s. These projects now face a wide range of long-term price scenarios and growing uncertainties. This means what may be profitable in today’s environment may no longer be tomorrow.

Operators seek to mitigate this risk by accelerating the payback periods for new investments and raising the return thresholds to account for additional risks. The current focus on smaller, incremental, and more modular projects, with access to infrastructure and the ability to be brought on faster, reflects this trend.

Long-term demand uncertainty, likely reinforced by short-term trends, remains a powerful restraining force and by far the greatest source of investment risk.

In current situation, nobody wins: The current energy price volatility is not good for consumers, investors, businesses, or governments

Adequate investment is needed for stable markets now and in the future. If investment falls short, it increases the risk of high-prices and high-volatility becoming the new standard.

Underinvestment threatens to undermine energy security in the short and medium-term and it can also stall progress on climate goals as demonstrated by the increased reliance on coal.

Prolonged cycles of energy price volatility are detrimental to economic growth. On the micro-level, it can affect individuals’ and companies’ costs and revenue streams, making planning difficult. At the macroeconomic level, volatile oil prices fan inflation, hinder investment, delay consumption of durable goods, reduce total economic output, dent equity returns, and entrench energy poverty.

The uncertainty surrounding future supply/demand can impact prices before the market is under/oversupplied. Delayed investment decisions and the increased reliance on short-cycle production, increases the uncertainty of where or if future production will be sourced. Concerns about reduced FIDs and lower investment today can raise current prices even if the current market is well-supplied.

Ways Forward: Increased Cooperation & Supportive Policies

To move forward and enable stable markets through the medium term, there needs to be intensified dialogue between, and supportive policies from, both producers and consumers. The traditional framework of energy markets is evolving, and market players and governments need to adapt. Energy trade is being reshaped by geopolitics, shifting demand hubs, historical underinvestment in some traditional supply regions (e.g., West Africa), and new business models by short-cycle producers.

Increased dialogue between suppliers and consumers, and data transparency are needed to ensure security of supply and market stability through the current energy crisis and the energy transition. History has shown that without market management, boom-bust price cycles prevail and wreak havoc on economies, particularly in regions that are still developing.

In addition to active and continuous dialogue, governments can help by providing regulatory and policy certainty, including those related to ESG. In many parts of the world, environmental policies and regulatory frameworks related to the energy transition are in flux. As a result, companies must consider the impact that future regulatory changes may have on the costs of compliance and returns over time. Unforeseen or newly introduced regulations can lead to higher costs and reduced revenues.

Consumer countries can support markets by sending clear signals about future demand, building and maintaining sufficient inventories, supporting long-term offtake contracts, and preventing prohibitive policies.

Meanwhile, producers can support markets by promoting investment. Operators need a certain level of assurance and regulatory certainty to invest in capital-intensive, long-cycle projects. They will be increasingly constrained in committing capital, or will require higher returns to do so, as risks evolve. Future supply must clear an acceptable hurdle rate that accounts for policy uncertainty, variable oil and gas prices, and, increasingly, carbon price assumptions.

Additionally, governments should base policies on realistic energy demand outlooks and to ensure adequate and affordable energy supplies during the transition. The energy industry needs more certainty from policymakers over penalties and incentives for future energy investments to ensure sufficient capital for all technologies is mobilized to meet the climate challenge. This requires government policies grounded in realistic assumptions about demand and disruption risks. In particular, governments need to ensure assumptions do not underestimate energy demand growth coming from the 80% of the global population in the developing world.

Conclusion

Today’s energy market is defined by uncertainty and volatility. It is hard to predict where markets will stand in a year, nevertheless, in 8 years. But decisions made today will impact the availability and affordability of future supplies. Increased dialogue with clear and decisive policies can help reduce the uncertainty inherent in a complex and integrated market. Low-cost resources and capital are available – but the investment environment needs to be de-risked and producers need incentives to re-invest. Adequate investment would help foster market stability, economic growth, and enable a just and orderly transition for all. All it requires is a commitment of capital, market transparency, and open dialogue between producers and consumers.

[Credit: International Energy Forum and S&P Global Commodity Insights]